Jay Fisher - Fine Custom Knives

New to the website? Start Here

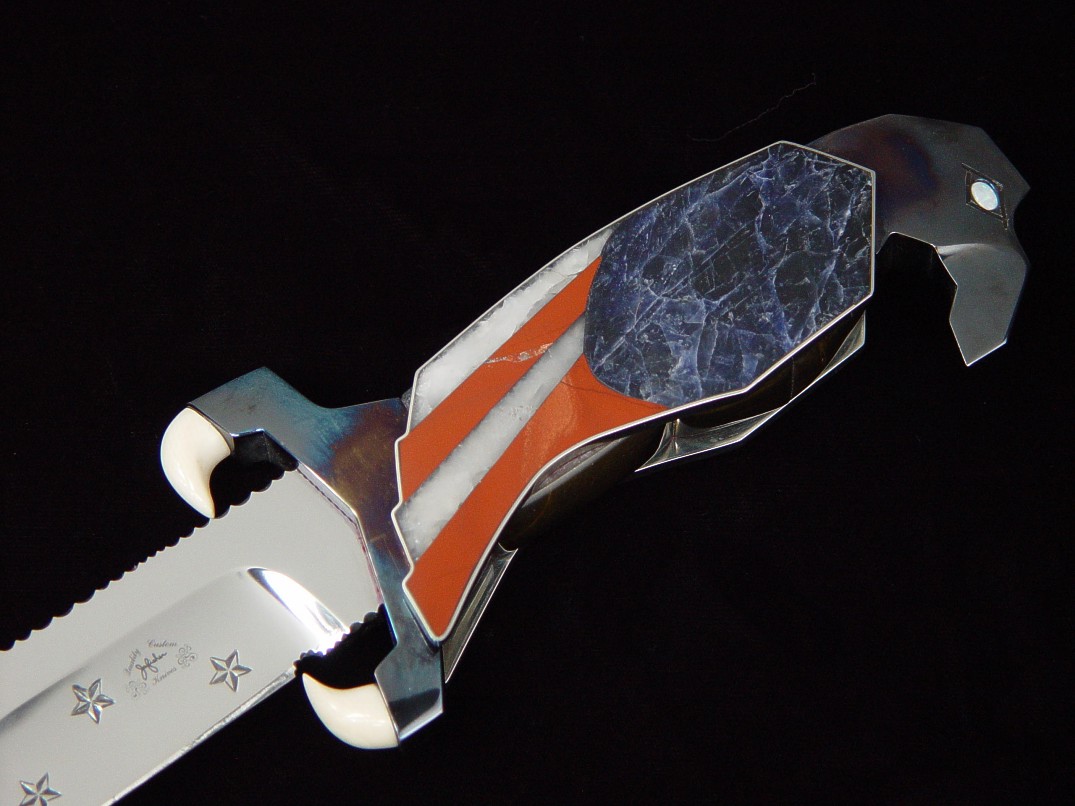

"Raptor"

Horn, bone, shell, and ivories used in modern custom and handmade knife handle and component construction offer visual interest, tactile security, or great beauty and value. This page is about these natural materials.

Notice! As of July 6, 2016, there is a near-total ban on elephant ivory sales in the United States!

Please click on the items in the list below to jump down the page to details of each item or species.

| Natural Animal Knife Handle Materials | ||||

| Antler | Horns | Ivories | Bone | Pearl, Shell, Coral |

| Deer Antler | Sheep Horn | Elephant Ivory | Animal Bone | Mother of Pearl |

| Elk Antler | Kudu | Mammoth Ivory, Mastodon Ivory | Jigged Bone | Gold lipped Mother of Pearl |

| Sambar Stag | Springbok Horn | Walrus Tusk | Giraffe Bone | Tiger Coral |

| Stag (Scales) | Impala Horn | Fossil Walrus Tusk | Oosic | Abalone Shell |

| Stag (Crowns) | Gazelle Horn | Wart Hog Tusk | Oosic, Fossil | Paua Shell |

| Caribou | Oryx | Hippopotamus Tusk | ||

| Special Treatments | Cape Buffalo Horn | Elk Ivory | ||

| Ox Horn | Whale's Tooth | |||

| Cow Horn | ||||

| Stabilized Horn | ||||

The history is rich. From the first time prehistoric man laced a bone handle to a piece of flint with some sinew, he realized the importance in this handle material. Bones, tusks, and antlers from living animals memorialized the hunt, perhaps personalized and anointed his knife with the spoils of his hunting efforts. There are good examples of carving ivory from as early as ancient Babylonia, 2300 B.C. The tradition of using animal parts for his handles continued throughout history, and continues today.

Tradition, beauty, texture, and value.

Usually, the choice to use horn, bone, or ivory is one of tradition. Most of us grew up carrying jigged bone handled pocket knives, and in my day, we even carried our knives to school. Every boy had his own knife, and occasionally we would find one that had been dropped, or lost, laying in the dirt around the playground equipment. We would often play what we called "chicken," where we would throw the knife between the feet of our opponent in turns, and move our feet to the landing point of the blade, ever closer, until either one of our feet got stuck with the point of the knife, or we chickened out. Usually, our knives were so dull, they wouldn't penetrate a canvas tennis shoe. Man, things have changed today! Most of us are familiar with a stag handled hunting knife. This is the knife style our fathers and our grandfathers grew up with. You didn't take a wooden handled butcher's knife on a hunt, you took a stag handled knife. Again, this probably hearkens back to prehistoric principles of the hunt.

The choice to use horn, bone, shell, or ivory is also one of beauty. Nothing looks like a piece of stag, furrowed and rough. Fresh elephant ivory is a beautiful solid creamy color, suitable for engraving, carving, or scrimshaw. Mammoth ivory can have stunning patterns in rich browns, reds, and even blues. The shapes of many antlers and horns left in the round lend themselves to handles, the forms compliment knives and sometimes modern stands and fittings. Shells can have stunning iridescent light play and a smooth lustrous finish.

The texture of many of these materials helps improve grip strength. Many horns, bones, and ivories become sticky when wet, thus improving grip security when working. The texture adds visual interest and contrast to a smooth and polished blade. The texture of a fine organic material makes a transition between the cold, inorganic steel blade to the living, warm, moving hand. The polished texture of ivory has a smooth comfortable feel, jigged bone is attractive and secure in the hand.

Value is one of the more modern reasons to use this material. Ivories are hard to come by, ancient ivories are a limited resource. Mammoth and mastodon ivory, fossil walrus tusk, and fossil Oosic are some of the most valuable and sought after knife handle materials. Some shells, coral, and pearl families are rare and expensive. Many of these materials increase the value of the knife dramatically.

The first problem with them is that all the materials listed on this page are somewhat porous, and this effects stability. There are lesser and greater degrees of porosity, and that helps with good choices for handle applications. Being porous and organic, these materials absorb moisture, loose moisture, absorb contaminants, salts, and soil. Extra care must be taken to keep the handle material clean and dry. Sudden changes in relative humidity (like moving from a damp forested environment to a dry air conditioned room) can cause such a variation in moisture content that the material shrinks and cracks away from bolsters, guards, or pins within hours.

Temperature also affects these materials radically. Putting a bone or ivory handled knife in the direct sun or under a bright display lamp for a couple hours can ruin it. Part of the problem is moisture content, but another factor is the coefficient of thermal expansion. Since the coefficient is much different than steel, movement can be outright extreme. Often, pins and epoxy do not prevent movement, and eventually the bone, horn, or ivory shrinks, checks, and cracks away from the pins, bolsters and tang. This does not necessarily mean the end of the knife. As long as the knife is kept reasonably dry, it should last in service.

Light can be another enemy. Many of these organic materials react to the long term exposure of light, sometimes bleaching and becoming flat in color and depth. Since they are usually laying on one side, the other side will not bleach, and then the knife looks like a different handle material was put on each side. On a hidden tang knife it can look as if it's been laying in the desert for a century. And the intensity of the light also adds to the effects of drying detailed above.

Sometimes, checking in ivory is an advantage. It testifies to the age of the knife handle, and elephant ivory is graceful and forgiving in its yellowing and checking. It's proof that it is indeed ivory, because replacements (like Micarta® and phenolic plastics) never change, age, or check.

Another disadvantage is toughness and hardness. Organic materials like horn, shell, bone, and ivory can easily be scratched, dented, scarred, and stained. Though some are tougher than others, they are not physically strong materials. Some are brittle, some are downright delicate so special care must be used in mounting them on the handle, and the knife and handle itself must be cared for with extra consideration.

Size and shape can be another limiting factor in knife handle design. Most of these materials are derived from curved pieces, and the geometry of the knife handle must incorporated these curves to exhibit the most from the handle material. Particularly, this can limit the width of the handle. Sections must sometimes be made thin to take advantage of the display area of the material, and this further threatens overall strength. That is why so many mammoth ivory handles, for instance, are used on smaller or folding knives. The curve of the tusk can not be fully applied to the handle flats if the handle is wide and large.

Legality: Some horns, bones, and ivory are banned! This takes some research, and you don't want some local or uneducated law enforcement person showing up at your home to confiscate your knife. This is becoming a serious issue, so it's best to avoid all organics that are restricted, like fresh ivory, rhino, walrus, tiger, or any other organics you are not absolutely certain are legal!

Hello Jay

I acquired two black rhino horns in 1982 pre import ban and would like to no if you have an interest, and or if I commissioned you to build

me a series of knifes and use them for the handles.

J.

Seriously, all rhino species are critically endangered, and there are less than 5000 black rhinos left in the world today (at the time of this

writing). I realize that you have old rhino horns, but do you have absolute proof of their origin? I'm certain you don't, for a slip of paper does not

physically date organic horn, and that's your first legal hurdle.

The first international ban on rhino horn trade was in 1975, and even today there are continual efforts to strengthen

management of rhino horn trophies and implements, which means lots of legal authorities confiscating, and fining, and imprisoning. Like walrus tusk and

recent elephant tusk, it's just not reasonable to make knife handles nowadays out of them without a lot

of headache. I don't want to be called to testify in your behalf about the origin of a knife handle I made.

There are much more durable and beautiful

handle materials! Have you actually seen rhino horn finished? It's

compressed hair (keratin) and rather boring and and not particularly distinctive or beautiful, and you

really can't tell it from a water buffalo horn. The interest then is the

romantic idea of the rhino horn, and not the

beauty or durability of the substance. In my world, ideas can be

inspiration, but the magic is in the process and execution, not the

suggestion that you wrestled a 3000 pound beast to the ground to snap off his only protection from

lions or other rhinos.

Knife handles aren't the only use of horn, bone, and ivory. I often incorporate these materials into my display stands, sheaths, and even as accent components in the knives themselves. Nothing looks as rich and organic as ivory, polished horn, shell, or coral. It is quite common to see a fork of an antler used to support or elevate a knife on a display stand, and though that is where most of us start in our quest to display a knife, an evolution of that process is inevitable in the finer works.

Horns and antlers have been commonly used in knife handle construction for many millennia. Along with wood, horns and antlers are probably the oldest knife handle material. Horn and antler can be left rough, polished, or carved, sometimes scrimshawed or textured. Though they are similar and often referred to in the same reference, there are some important differences.

Horn is mostly a derivation of hair, actually hollow sheaths of keratin, tightly condensed and packed in a solid growth. Horns, such as cow horn and buffalo horn, are not shed annually, and commonly last the life of the animal. Horns are usually more dense than antlers.

Antlers are a porous bony appendage that are shed annually, so antlers are a renewable resource. Elk, mule deer and white tailed deer are good examples. These sheds can be a valuable find in the forests of our country, and many hikers go out in the early spring just to gather shed antlers. Antlers are usually more porous than horn. Some antlers are better than others.

Often, the terms horn and antler and stag are interchanged, which can cause some confusion. Each one deserves some special attention:

Ivories are animal teeth. Ivories and tusks are unusually dense, some of the densest, hardest animal parts and remains. They are much less porous than bone, therefore last longer, are less apt to absorb liquids, and polish better. They are definitely a step up from bone and antler, but cost considerably more. However, they are not impervious to moisture damage, expansion and contraction, staining, and separation from the knife handle.

I read an ad copy on one web site and the claim is when you buy a custom carved ivory knife handle, "you will own an exclusive work of art that will defy time." What? Ivory shrinks, dries, checks, cracks, stains, and yellows. Time is an enemy of ivory, it will not defy time in any sense of the word. Such claims like this do our business and tradecraft a huge injustice. What handle material will defy time and even outlast the blade? Why, gemstone, of course.

Ivories have traditionally been the most favored of animal parts for knife handles, jewelry, and accessories, so much so that the trade in ivory has reduced some animal species to near extinction. There is a lot of regulation and restrictions on ivory use, and documentation of the origin of certain ivories can be tedious, only for the supplier and maker, not usually for the knife client or collector. Overzealous bureaucrats have even confiscated Mammoth ivory handled knives believing the ivory was from recent elephants. Maybe they were trying to protect the Mammoths from extinction... oops, too late.

Here are the types with details:

Elephant ivory in knives is now finished.

As of July 6, 2016, new elephant ivory-containing items are banned from sale in the United States, and older stock with elephant ivory is severely restricted. The Department of the Interior's US Fish and Wildlife Service has extensive details on their website, but it's clear that this is an effective ban on elephant ivory sales. Clearly, elephant ivory in knives, knife handles, sheaths, components, and accessories is finished in the United States.

How this looks for knife makers and collectors and owners of knives is not good, if they prefer ivory, horn, bone, or natural organic materials. No new knives with ivory can be made and sold. All ivory that is not ancient must be accompanied by extensive paperwork and documentation, or the risk of confiscation is assumed. All other ivories will be subject to scrutiny; extensive laboratory examination must be made to distinguish elephant ivory from mammoth or mastodon tusk, or modern wart hog tusk, hippopotamus tooth, or other materials similar in appearance. The topic can be summed in this interview and questionnaire I gave to Michael Haskew of Blade Magazine on August 23, 2016. His questions and my complete answers follow:

Numbered questions by Mr. Haskew, of Blade Magazine (August 23, 2016)

1. Tell me about your company. What do you do exactly? How long have you been in business

I am and have been a full time professional knifemaker for 28 years and have been making custom and creative knives for combat professionals, knife users, and collectors. I’ve been making knives for 38 years.

2. What does the Fish and Ivory Wildlife Rule that went into effect July 6 mean for you and your business?

It’s important to understand that this is a near total ban on elephant ivory sales. Clearly, elephant ivory in knives is finished. I won’t be using any elephant ivory, and mammoth ivory I use will be very limited to only very dark, stained, and obviously ancient ivory.

3. Are you restricted in where you can sell ivory now?

Not sure of this question; since it is now August, and all current elephant ivory sales are restricted or banned, according to the de minimis exception, listed on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife International Affairs website detailing the new laws. Elephant ivory without detailed provenance is now illegal to sell. All new elephant ivory hand crafted items are now illegal to sell.

4. Do you know of any recent raids or confiscations that have taken place? Could you tell me about the evens surrounding them?

No.

5. Are you cutting back on stocks of ivory and concentrating on other materials instead? If so, what other materials and why?

Unfortunately, this ban and severe restriction of ivory sales does not just affect elephant ivory. I haven’t made or sold a knife with elephant ivory in many, many years, but there are many types of ivory that resemble elephant ivory. These are not banned, but are fish and wildlife officials and law enforcement agents going to be carrying around long-wave ultraviolet lamps to determine mineral inclusions of ancient ivory, along with a testing standards kit, and a ten-power magnifier to determine if mammoth ivory is not elephant ivory? Oh, and don’t forget, they need to carry along a photocopy machine, with variable contrast and a ruler and protractor to measure Schreger lines for this determination. Since this is unlikely, venues, dealers, and websites may ban all ivory types, whether wart hog tusk, mammoth ivory, or hippopotamus tooth, since determinations may be difficult and costly.

6. What can knife collectors expect to see in the way of handle materials in the future?

Because of the ban, non-elephant ivory and ivory-like items may be less desirable. Collectors and knife owners simply don’t want the hassle of the threat of confiscation, or having to possess extensive documentation and provenance to prove their handles are legal. In tactical and working knives, manmade materials and plastics will dominate, but exotic woods may be next on the horizon of control and restriction. In my own art and profession, gemstone has been a mainstay for decades, and I believe it will continue to be the premium material for knife handles in the future. It’s strong, extremely stable, and strikingly beautiful. No living species, plant or animal, will be directly endangered by its use, and in most cases, it will outlast the knife itself.

7. How difficult is it to prove that your ivory inventory was bought before a certain year? What year is the cutoff now? In general, how difficult is it for anyone to find the necessary information?

It’s fairly easy to find the information about the ban on the US Fish and Wildlife’s website. The information is not good for owners of any elephant ivory.

8. What kind of advice would you offer to knifemakers and knife buyers in terms of the new rule when it comes to the ivories they have on hand in either unattached scales or ivory knives in general?

Unfortunately, because of the last rule in the de minimis exception, elephant ivory currently not mounted on a finished knife made before July 6, 2016 cannot legally be used to put on a knife and sold. It’s pretty clear. So elephant ivory scales are now valueless. Even if a knife with elephant ivory or just the elephant ivory is given away, it needs to have accompanying documentation. If a knife was made before July 6, 2016, it must have all of the documentation and provenance accompanying it to be sold. Also, don’t be surprised if the knifemaker is asked to prove when the knife was made to satisfy this rule, which is very hard to establish and defend in a legal setting.

What should collectors buy and not buy due to the new rule? What should knifemakers buy and not buy?

It’s probably not wise to saddle a knife client and owner with the hassle of

extensive paperwork, proof of origin, and dated provenance to continually

prove his ivory was of legal origin.

Collectors and makers both need to stay away from elephant ivory. The basis

of the law has good intentions, to stop the slaughter of elephants and

prevent diminishing herds. There are much more stable, common, and

accessible knife handle materials. It’s not worth criminal or civil

penalties and jail time.

9. Any other comments you might have would be greatly appreciated

Ivory is now finished in knife handles in the US, as this is a near total ban. No new elephant ivory-handled knives can be legally made and sold. Consider this shocking fact: even though ivory in handmade products is banned, United States hunters are allowed to bring up to four “trophy” tusks per person, per year into the US. How does this help the dwindling elephant herds? This is our government at work.

Officials, law enforcement, and Game and Fish will be confused by the many ivory types available, including wart hog tusk, hippopotamus ivory, mammoth, mastodon, and walrus. Adding to the confusion are materials that look like ivory: shell and bone, stag and animal horn and manmade materials like acrylic and Micarta®. All of these must be accurately and completely detailed and identified with accompanying documentation when necessary. If this direction continues, it wouldn’t surprise me if exotic wood species bans are next.

Animal bone has been used on knife handles since the dawn of time. Whether to represent the hunt and quest for game, or because it was a willing and workable raw material, or perhaps because ancient man just wondered what to do with all that extra bone lying around, it found its way to the handle. Bone is easily worked, plentiful, and fairly durable. On the modern custom knife, though, it has some problems. First, it is very porous. That means that it absorbs pretty much anything it contacts. Perhaps in ancient times, the tissues and fluids and sweat it encountered would help it stabilize, while imparting a weather resisting patina. Nowadays, no one field dresses their hamburger, or scrapes a hide to make boots for tromping through the snow after mammoth. So the bone is left to dry out, absorb atmospheric moisture and fluids from the hand, and is subject to continuous heating and cooling of the days and seasons. So, being so porous, it expands and contracts extensively, and eventually works itself loose from fittings, cracks around pins, fights any method of attachment used to fix it to a knife tang. It is much more unstable than ivory, and is therefore usually used on the cheapest of knives. Bones mounted on knife handles are often jigged. Jigging in this context is a word that comes from Scotland, and refers to any mechanical contrivance that operates by repeated jerky and reciprocating motion. So jigged bone is named for the jigging machine that cuts it. The cuts in the bone give it some tactile purchase, especially when wet, offer some visual interest, and hide grainy porosity in the finished surface.

The sea has offered us some beautiful materials for knife handles and adornment. These organics can include fish teeth and bones, but their use in knife handles is rare. Pearl, shells, and coral are abundant and moderately durable once mounted on the knife.

Thanks for being here!

I'll add new photographs and descriptions of my horn, bone, ivory, and shell handles, components, fixtures, fittings, and artwork as they become available.

| Main | Purchase | Tactical | Specific Types | Technical | More |

| Home Page | Where's My Knife, Jay? | Current Tactical Knives for Sale | The Awe of the Blade | Knife Patterns | My Photography |

| Website Overview | Current Knives for Sale | Tactical, Combat Knife Portal | Museum Pieces | Knife Pattern Alphabetic List | Photographic Services |

| My Mission | Current Tactical Knives for Sale | All Tactical, Combat Knives | Investment, Collector's Knives | Copyright and Knives | Photographic Images |

| The Finest Knives and You | Current Chef's Knives for Sale | Counterterrorism Knives | Daggers | Knife Anatomy | |

| Featured Knives: Page One | Pre-Order Knives in Progress | Professional, Military Commemoratives | Swords | Custom Knives | |

| Featured Knives: Page Two | USAF Pararescue Knives | Folding Knives | Modern Knifemaking Technology | My Writing | |

| Featured Knives: Page Three | My Knife Prices | USAF Pararescue "PJ- Light" | Chef's Knives | Factory vs. Handmade Knives | First Novel |

| Featured Knives: Older/Early | How To Order | 27th Air Force Special Operations | Food Safety, Kitchen, Chef's Knives | Six Distinctions of Fine Knives | Second Novel |

| Email Jay Fisher | Purchase Finished Knives | Khukris: Combat, Survival, Art | Hunting Knives | Knife Styles | Knife Book |

| Contact, Locate Jay Fisher | Order Custom Knives | Serrations | Working Knives | Jay's Internet Stats | |

| FAQs | Knife Sales Policy | Grip Styles, Hand Sizing | Khukris | The 3000th Term | Videos |

| Current, Recent Works, Events | Bank Transfers | Concealed Carry and Knives | Skeletonized Knives | Best Knife Information and Learning About Knives | |

| Client's News and Info | Custom Knife Design Fee | Military Knife Care | Serrations | Cities of the Knife | Links |

| Who Is Jay Fisher? | Delivery Times | The Best Combat Locking Sheath | Knife Sheaths | Knife Maker's Marks | |

| Testimonials, Letters and Emails | My Shipping Method | Knife Stands and Cases | How to Care for Custom Knives | Site Table of Contents | |

| Top 22 Reasons to Buy | Business of Knifemaking | Tactical Knife Sheath Accessories | Handles, Bolsters, Guards | Knife Making Instruction | |

| My Knifemaking History | Professional Knife Consultant | Loops, Plates, Straps | Knife Handles: Gemstone | Larger Monitors and Knife Photos | |

| What I Do And Don't Do | Belt Loop Extenders-UBLX, EXBLX | Gemstone Alphabetic List | New Materials | ||

| CD ROM Archive | Independent Lamp Accessory-LIMA | Knife Handles: Woods | Knife Shop/Studio, Page 1 | ||

| Publications, Publicity | Universal Main Lamp Holder-HULA | Knife Handles: Horn, Bone, Ivory | Knife Shop/Studio, Page 2 | ||

| My Curriculum Vitae | Sternum Harness | Knife Handles: Manmade Materials | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 1 | Blades and Steels | Sharpeners, Lanyards | Knife Embellishment | ||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 2 | Blades | Bags, Cases, Duffles, Gear | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 3 | Knife Blade Testing | Modular Sheath Systems | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 4 | 440C: A Love/Hate Affair | PSD Principle Security Detail Sheaths | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 5 | ATS-34: Chrome/Moly Tough | ||||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 6 | D2: Wear Resistance King | ||||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 7 | O1: Oil Hardened Blued Beauty | ||||

| The Curious Case of the "Sandia" |

Elasticity, Stiffness, Stress, and Strain in Knife Blades |

||||

| The Sword, the Veil, the Legend |

Heat Treating and Cryogenic Processing of Knife Blade Steels |