Serrations and Sharpening on Modern Handmade Knife Blades

"Vampire" Serrations on this

Arctica

This page is about serrations, particularly on the

modern handmade and custom knife, specifically on my knives created here

in Sharp Instinct Studio in my sole authorship knives.

I'll detail a little history and description of serrations and why they

work and how they apply, with descriptions and photographs of my own

serration styles and applications. I will explain why I've chosen a

particular type of serration for a specific application, and how they

work in that application. I'll describe the limitations of their use, considerations

for individual knife blades, and how to sharpen the serrations on my knives specifically.

I'll detail current and accessible sharpening tools and their features

so the owner of one of my serrated knives can sharpen his own serrated

edge sections. I do this as part of my commitment to my tradecraft, art,

and professional service to my knife clients. As with most other pages

of this site, when you are done reading this, I promise you will know

more than most people, knife makers, and knife manufacturers about

serrations on modern hand knife blades.

For detailed descriptions and discussion of other knife maker's or factory knife

serrations, please contact those other suppliers and makers.

Page Topics

Canine serrations on the top edge of this

Triton

"

Sasserides" Bread Knife with Mini-curtain serrations

The word serration comes from the noun and adjective

serrate. Serrate is probably a imitative variation of the Latin

word serra, which means saw. The word sierra is a

variation of the Latin word, so it's no wonder saw-toothed mountains are

named sierras. The study of serrations is a fascinating

subject, and naturalists have wondered for centuries how animal and

insect teeth, as well as some plant leaf edges cut so well. Seen in modern

photomicrographs, it is usually tiny serrations that are the

contributing factor to the keen cutting ability of sharks teeth, saw

grass, and even corn leaves and dinosaur teeth. Nature's serrations

work, so we simply imitate the natural world with our own version on the cutting edges of

knives.

Many modern knives have serrated blades. The reason for serrations is

to aid in cutting, ripping, and tearing

through tough materials that resist cutting with a regular smooth blade edge. In theory, if a regular, straight

cutting edge of a knife blade is truly sharp, serrations should never be necessary. The reality is, though, many

abrasion-resistant surfaces like plastics, hardwoods, textiles, and other tough modern materials are better cut

with the ripping action of serrations.

The reason serrations work is because of the tremendous pressure applied to very small cutting edges or advancing

teeth surfaces. I'll probably delve into this in greater detail in my book, but the concept is that through a combination

of light percussion and advancing narrow cross-sections, a tooth can have a more aggressive cut than a smooth blade. Of

course, a regular straight cutting edge should be clean, efficient, and smooth, and the two types together make for a very

useful knife that can cut through a wide variety of materials, as

long as the knife maker has done his job right.

When I first started making knives for military combat applications,

my military clients insisted on serrations that work. They

were, frankly, tired of owning and trying to use knives that had serrations that were not sharp, keen, or aggressive

enough. When I

informed them that in order for serrations to work well, they must be thin, and therefore

had a greater potential to break, their

request was simple: "make a serration that works aggressively, and even if I break off a tooth, the serration keeps on

working, cutting, ripping, and tearing." This is what my serrations

do.

Page Topics

Very aggressive hammerhead serrations on

this PJLT

There are two camps on serrations. Some like them, some do not.

Both are correct.

Whether a knife has or (in the case of custom knives)

will have serrations on the blade bears careful

consideration. On my Blades page, I discuss this briefly,

and here is a more detailed version. I'll give the

limitations first, and then the advantages:

Serrations: Limitations and Considerations

- Serrations subtract from the overall regular straight cutting edge length of the knife.

If your knife has a 6" blade,

this is measured (in most states) from the tip of the point to the

front face of the bolster or guard face, and not the actual cutting edge length.

So the cutting edge may be 5.5"

long, and you decide on 2" of serrations. You are now left

with a 3.5" regular edged knife blade. On shorter blades, this

is very noticeable, and can even prohibit the use of serrations

altogether. A knife that has a regular cutting edge length of one

inch is hardly worth a handle, unless you want a box cutter. Please

consider that a fixed blade box cutter with replaceable double ended

utility blades has a cutting edge length of over 1.25" and the more

common retractable version has a cutting edge length of 1.125"!

- Serrations can make a knife harder to insert and tricky to remove from a sheath,

depending on their design and location. Careful design cannot always help, and you

might find your sheath welts ripped up from the teeth over a period of time.

This is not only noticeable in leather welt sheaths, but even kydex

and aluminum framed sheaths can suffer from abrasion and ripping by

serration teeth.

- Serrations can not be used on the top spine of one of my

tactical knives if it is to reside in a locking sheath. This

is because the location of the locking mechanism is in the

direct line of contact of the serration teeth if they are

placed here, and the two will destroy each other. Serrations

on a spine of one of my knives must be coupled with a

tension fit sheath, which is less secure. A newer alternative

comes from my development of my counterterrorism knife sheaths. This

is a hybrid of my tension and locking sheath, simply called a hybrid

tension-lock sheath. This particular sheath uses tension of a

component that does not contact the serrations, but it is not as

secure as a locking sheath.

- Serrations on the spine of any double-edged knife may

cause other issues. For instance, if the owner wants to bear

down on the regular straight edge of the knife blade, or

wants to apply spine pressure with his thumb or hand

(typical for tanto knife secondary points), obviously this

can't be done of the serrations are there.

- Serrations on the spine of a knife require the knife to

be double-edged. This means double ground, often double

hollow ground, which can remove a good cross-section of the

spine. To have the same spine strength as a single-edged

knife blade, the blade must be wider. If kept the same

width, the knife is simply weaker in the spine because there

will be less metal there.

- Because serrations on the spine of the knife create a

double-edged knife, certain countries may not allow these knives to

be shipped or possessed. For instance, Australia prohibits the

import of double-edged knives altogether.

- Because serrations require brute force to rip, tear, and

cut, most of them should be called rip teeth, and they are usually placed near the

ricasso, not at the end of the blade. That way, more force at the heavier cross-sectional

geometry of the blade will support their use. If serrations

are put near the blade tip, it's possible that when they

snag, the force of the hand with the leverage of the blade

length may offer enough force to snap of the tip of the

blade, the weakest part of every knife. Sometimes, in

specialized knives, serrations are located on the top edge,

such as in specialized chef's knives, but not usually in

tactical combat models. Considering this, serrations on the

top edge of a double-edged knife should not start at the

tip, but slightly behind the tip for greater tip strength.

- The serrations may hang up, snag, and seize in cutting when you don't

want them to. You may be using your regular cutting edge, and have

the material you're cutting fall into the serrated part of the blade,

hanging up or snagging unexpectedly, and perhaps

ripping up a clean cut or causing hesitation that is undesired.

A finer serration or specially designed serration may reduce hanging

and tearing, but not always.

- The tip of the teeth of narrow serrations may break off, because sharp teeth

must be thin teeth. One of the military requirements I've had

is to make a tooth that will keep cutting even after broken. This means a thinner cross section, to make a more aggressive tooth.

- Serrations may be difficult to sharpen. They often are,

but thankfully I've included instructions to do that on this

very page. I use special equipment (diamond abrasive based cutters) to

make them and hone them, and that same equipment is not available in the field,

but diamond abrasive coated rods and tools are. Note that each type of tooth is different,

and requires its own sharpening regime.

Serrations: Advantages and Considerations

- Serrations can allow ripping or tearing through

extremely stubborn materials that a straight edge can not.

If a knife user encounters hardwoods, bone, horn, plastics,

textiles, and even tissue that resist cutting with a

straight edge, a well-designed and sharp serration can allow

him to rip through. This is the main advantage of serrations

on knives and it is substantial. I've even had military

clients rip and saw through the aluminum on a wrecked APC to

affect a rescue with serrations on my knives.

- Serrations can clear a cut. When a regular, straight

cutting edge cuts, it simply displaces the material from

itself, separating the material, but not removing it. So the

side pressure and potential for pinching the knife blade

increases as the cut deepens. Having a thin blade helps, but

the material is still there, pressing on the sides of the

blade. It's interesting to note that a hollow ground blade

has the thinnest cross-section, so that helps. Even the

thinnest blade does not remove material from the cut, and a

serration may well do that. It tears and rips through,

dislodging particles from the material, helping to clear the

cut. No where is this more noticeable than when ripping

hardwoods with serrations.Also, because the cut is rough,

the material being cut can help to separate the gap.

- Serrations can pierce. They can simply start a cut that

would be difficult to start with a slick, smooth, and sharp

blade. Some polished or very smooth surfaces can be

difficult to start cutting, and the serration point can

pierce these surfaces, allowing a traditional edge cut to

commence.

- A seldom considered feature of well-designed serrations

is that they will prevent an enemy from grasping a blade.

This may seem obscure, but this feature in serrations has

been known by Armorers, weapon makers, and warriors for

literally millenia. When a gloved hand tightly grasps a

straight, smooth blade, no matter how sharp the cutting edge

is, if it is grasped tightly, and the blade does not move

along the length of the blade, the edge simply can not cut.

In the warrior's combat knife, this is a devastating

reality. The blade can be grabbed tightly, and perhaps even

taken from the warrior. How serrations can prevent this is

that, if they are well-designed, grasping the knife at the

serrations will pierce even the best gloved hands, and the

enemy will have to let go. In antique swords and parrying

daggers, this was a distinguishing factor that prevented

grasping one another's blade.

- A serration can save the rest of the edge, the blade,

and possibly even the knife! For a simple illustration, try

cutting through a small piece of oak with a straight edge,

specifically cross-cutting (across the grain, not along it).

Even the sharpest straight edge will slide along it, and

then the temptation will be to start chopping on the wood

like with an axe. This is not how a thin, sharp cutting edge

should be used, and the likelihood of breakage is

substantial. I know of plenty of knives that have been

broken or had their edges chipped because they were used for

chopping, instead of cutting. This does not only apply to

woods; I've seen blades chipped while chopping bone. If the

serrations are present, and they work, the temptation to

chop with a knife is often averted, saving the blade as the

serrations do the cutting necessary.

- Serrations extend the cutting surface of the actual

edge, sometimes by many factors. A straight length of

blade is measured simply by the distance along the edge.

A serrated knife, because of the many curves, in and out

of the blade axis, actually increases the cutting edge

length significantly. You simply have more edge to cut

with on a serrated blade section. This adds to the life

of the edge.

- Serrations may outlast the regular knife blade. This is

often the case, due to several factors. The serrations are

simply less used than the regular straight edge length, so

do not wear as quickly. Also, serrations usually wear on the

higher points, that is, the most protruding parts of the

teeth. So the deeper edges in the serration simply see less

wear. Because well-designed serrations have thicker profiles

and cross-sections than straight edges, they last longer.

Sharpening is less often, and less of the serration is

sharpened away.

- Serrations can help to catch, trap, or snag

materials and items that are easily pulled away from

smooth, straight, slick, and sharp blades. Fibrous

materials like rope, line, or even some skins can simply

slide away from a smooth blade, but serrated blades bite

into the group of fibers and can help to trap and cut

them without sliding.

- Serrations can cut effectively, even when more dull

than the straight edge. This is because more pounds per

square inch can be applied to a smaller area, combined

with somewhat protected areas of the serrated edge.

Usually the most frequently dulled parts of the

serration are the points or most outward projections of

the serrations, which can leave the deeper edges of the

serration sharper for a longer period of time.

- Specialized serrations can be designed and made to cut

aggressively in one direction and release in another. This

is the function of canted (angled) serrations on knife

blades. This, in design concert with mechanical aids to

apply pressure in the cutting direction such as quillons,

mid-bolsters, and sub-hilts, can mean a very efficient

cutting direction and device.

- Serrations look more aggressive. Though I do not

include serrations simply for the visual punch, they do

add to the appearance of a blade in stylistic fashion.

Like some mirror polishes, on tactical combat knives,

they may add to the threatening appearance, perhaps

intimidating and threatening an enemy more than a slick,

smooth blade. Of course, this is not the main reason to

include them on a knife, though some factory knives are

made this way just to make the knife look more

aggressive. They must, as a primary consideration, add

to the cutting abilities of the knife.

- Serrations have derivatives, like line cutters,

hookblades, and gut hooks. These specialized features allow

specific results. A line cutter may be designed so small

line (such as monofilament) may be trapped and cut with one

hand, while the line slides down the arm and handle and is

snagged and sliced in one motion. Without a line cutter, one

hand must hold the line, and the other locate and slice with

the blade using a sawing motion. A hookblade is a

specialized blade that may allow cutting on the inside

curve, while protecting another area of contact. This has

been effective in certain rescue knives, where a hookblade

feature can be used to remove a wetsuit from an injured

diver without cutting his skin. Another application would be

extrication and the slicing of seat belts while not cutting

the victim. Clothes and even boots can be removed in

emergency medical care of the sick and injured without

injuring the victim with a knife blade. Gut hooks, used in

hunting knives, can be used to slice the skin of an animal

while gutting, yet prevent cutting the internal organs which

can spoil the meat. All of these features can be interpreted

as derivatives of the serration, or modified blade edge.

Page Topics

Canine serrations on the upper cutting edge of this

Lynx

Tough and useful Hammerhead serrations on this "

Raijin" Counterterrorism Knife

Just like all the other parts, components, and features of a fine handmade knife, serrations also differ

from factory, manufactured, or boutique shop serrations. A close look at any serration will give a clear and

distinctive knowledge of these differences and how they affect performance, service, trust, and value.

There is a major determinant factor between mass produced, factory,

manufactured, or even small boutique shop serrations (even if the shop

is named for a singular knifemaker) and serrations made by a custom

knifemaker. That huge singular factor changes serrations simply from

rough parts of a cutting edge to instrument-sharp adjuncts that amplify

the cutting ability of the knife by many, many times. The factor?

Mass produced serrations are created by a wheel,

a diamond coated serration wheel that has a corrugated surface and is

coated with diamond abrasive in nickel plating. These wheels produce a

generalized serration profile, typically just some waves, and the

serrations are shallow, not pointed, washed over, unsharpened, and

generally dull. They are always shallow.

Handmade serrations are made one at a time, by hand, with

a file. This is done before heat treating the steel blade,

followed by dressing by hand, individually after hardening and tempering

the blade, followed by singular finishing, polishing, and sharpening

techniques for each tooth and each depression, each convex and each

concavity in the serration profile. This results in a crisp, clean set

and arrangements of cutting edges throughout the length of serrations.

Every micro face, every thousandth of an inch is a cutting tool: razor

keen, with crisp, pointed apexes, chisels, and hooks. They are deep and

effective.

Some more problems with factory serrations:

- Factory serrations are usually ground from one side of the blade. This may seem unimportant, but I

believe it is a substantial difference than fine handmade serrations which are

ground from both sides of the blade. The reason this

is done is because it is cheap, like most things factory knife manufacturers do.

Well-made serrations created from both sides mean

careful registry and alignment must take place on each tooth, so that the tooth valleys and points match each other

and prescribe a line down the axis of the cutting edge. This makes a much sharper serration because the included

angles of two-sided serrations are almost always lower than one side serrations.

- Factory serrations are harder to sharpen.

You might think that being only on one side would make

factory serrations simple and easy to sharpen, but this

is not the case. Lots of material will have to be

removed from the one side of the blade where the factory

serrations are machined in order to achieve and maintain

a lower and sharper angle. With well-made double-sided

serrations, a few quick strokes are all that is

necessary to tune up the edges and points since they

have less surface area to cut away.

- Factory serrations are uneven.

Since these serrations are cut by dressed and formed

wheels, usually under automated processes, it's only

natural that the diamond plated grinding wheels wear down, and they

don't wear evenly. So, if your factory knife is early in

the production run, the contour of the serrations will

be a bit more even, but if it is later in the wheel's

life, they will be uneven and poorly defined. Fine

handmade serrations are each meticulously laid out by

hand, and tuned to each other for an even fit. While the

handmade serrations are hand-made, they are much crisper, angular

and agressive.

- Factory serrations are never crisp or well

defined. This is due to the process limited by

the machining technology. A grinding wheel, whether it

is silicon carbide, aluminum oxide, boron nitride, or

diamond coated nickel on steel or phenolic substrate

lacks extremely sharp, punchy and well defined valleys,

so the points on the serrations are always rounded and

softened. Contrast this with fine handmade serrations

which are clear and sharply defined because each cut is

individual and independently cut and each peak comes to

a definitive point. A crisp point means instant biting

and trapping, one of the main reasons for serrations in

the first place.

- Factory serrations do not extend up the

termination of the grind. Since factory

serrations are made by a machine alone, they can not be

deeply machined into the grind termination near the

ricasso. What this means is that they must be located

where the knife blade is absolutely flat and of uniform

thinness. In order to do this, the factory knife is not

radiused or contoured at the termination, it is

straight, flat, and squared off, making the blade to

handle junction weaker. The factory serrations also must

be moved away from the termination area, making them a

bit further from the handle. In some cases, this means

less leverage and less serration length overall. With

fine handmade serrations, the placement can be up nearer

the termination, even into the termination with

substantial strength and cross sectional thickness at

these first important teeth. This is most easily noticed

when viewing the knife blade from the side.

- Factory serrations have many convex

profiles. This is, again, due to the

constraints of manufacturing. Wheels used to cut these

serrations can not have deep valleys or peaks, only a

slight variation of the two. So the design of the

grinding wheel surface is simplest to have a combination

of convex and concave edges. Unfortunately, a convex

serration edge is the hardest for the knife owner to

sharpen, and must be done with tiny, narrow dressing

sticks, carefully aligned. Though convex serration

profiles do have their place, for most serrations, they

are not the ideal. Like a knife edge, a hollow ground or

concave edge has the lowest sharpening angle and thus,

the sharpest edge.

- There are never any points on

factory serrations. Looking at the serrations below,

you'll see extremely acute points on each tooth,

particularly in my Vampire style. This is due to my

history of making knives for military combat and rescue

use. My military clients request serrations that work,

even if the tooth is broken off. They are tired of

serrations in name only, where a few gentle curves and

valleys seem to be thrown on to the blade as an

afterthought. They don't bite, they don't grip, and they

don't tear and rip like serrations should do. Sharply

pointed serrations do, and they are the most aggressive

you will find. In all the years of making knives, I've

never had anyone ask for "gentle serrations that are

just a little more coarse than the straight cutting edge..."

- Factory serrations are never canted, angled, slanted, or arranged to accommodate

the knife handle, use, fittings bolsters or reinforcements. In fine handmade knives,

the serration works with the handle and blade design for specific cutting force application.

For instance, in many of my Patriot pattern and knives with mid-bolster handle arrangements (see the

Minuteman EL below), the canted serrations are designed to cut on pull and

release on push. This

is distinctly custom and based on the knife owner's use and requirements, something not offered

on factory knives, boutique shop knives, or poorly made knives.

- Factory serrations may be soft!

This is a seldom discussed fact about factory or poorly

made knives with serrations. A knife blade is (or should

be) roughly ground, with most of the material removed

from the blade, all holes drilled, all machining that is

to be done on the blade completed, and then followed by heat

treating (hardening and tempering). That means that the

serrations should also be machined, filed, cut, ground,

and shaped BEFORE heat treat, followed by hand-polishing and simple

sharpening after. This way, the serrations retain the

temper of the blade. In poorly made serrations, they are

machined and ground AFTER heat treating the blade, which

can overheat the serrations, losing the temper. This is a

particular concern because of the high speed of the wheel that cuts

them. A thin

and narrow section of the serration (the points or the

very cutting edges) will be the first to lose temper and

soften. This is another reason factory serrations are

left without thin areas, because they may bend in use

due to loss of blade temper! In fine handmade

serrations, only the sharpening occurs after heat treat,

and in my knives, I finish grind and polish under water to keep the

blade cool and preserve the hardness, and each serration cutting

surface is sharpened by hand. The serration is

harder, more wear resistant, and (in stainless tool

steels) more corrosion resistant, and better all around.

Page Topics

Angled canine alternating tooth serrations on this

Minuteman EL

There are many different types of serration grind, profile, and type

of tooth and edge surface, even on my own knives, much less other knives

by other knife makers, factories, manufacturers, or sources. I can only

speak to my own serrations and my own experience making knives for over

30 years. There are many factors within my own knives that determine

serration type, style, length, and design.

What a knife is expected to cut is one factor of serration design. The length of the serration

available on the knife, the placement of the serration run, and the

angle of the serration grinds and teeth are all important geometric

considerations. I also consider the steel type, main grind

geometry, handle support features, corrosion resistance, and sharpening

service factor of serrations to produce and provide viable, useful, and

dependable serrations that can be serviced by the knife owner. Because

of all of these factors, serrations and their geometry varies, sometimes

greatly, even among my own knives.

My Predominant Serration Types

- The most popular serration style I create is my

Vampire

rip tooth serration. The Vampire consists of alternating diameter

of grinds (yes, just like a blade, a serration has a grind), and when

you examine a pair of these grinds, the protruding teeth looks like the

grimace of a long-toothed old Nosferatu. The key to the aggressive

nature of these serrations is the alternating sizes of the grinds. No

tooth is the same size, so each tooth will attack the material in a

slightly different location, which makes for very aggressive cutting and

ripping. This type is the most requested type of my serrations, and most

of my military and professional grade tactical combat knives that have

serrated blade areas have this type. The Vampire is easily serviced and

maintained, so field sharpening is possible as a regular service aspect

of the knife. Example below.

- A variation of the Vampire is the

Canine.

Like the Vampire, the Canine has alternating grind geometries, but the

sizes are distribute in a two-to-one or two-to-two grouping instead of a one-to-one or

alternating pattern. So the pair of two small grinds placed between the

larger grinds gives the appearance of a dog's or wolf's front mouth, two

large canines separated by smaller teeth, thus the name. It is a more

aggressive pattern than the Vampire, and can be suited to longer runs

along the blade length. It, too can be hand-sharpened in the field as

part of the regular service aspect of the knife. Example

below.

- A simpler version of serrations is my

Barracuda.

The Barracuda, just like its namesake, has an evenly sized run of small

teeth for a smoother cut than the Vampire of the Canine. This is not as

aggressive as the previous two, and lends itself well to even cutting

with less ripping. Less ripping and tearing means less hanging or snagging in the

cut, so this is an easier serration to use as it requires less force.

The Barracuda can be easily sharpened in the field. Example

below.

- Smoother still, yet very aggressive is my

Micro-Blade

serration. The micro blade consists of separated serration grinds with

small sections of regular blade length between them. It is a serration

that excels in smoothness, with less ripping, and can cut a wider

variety of materials with limited tearing, ripping, and hanging. It's a

great adjunct to specialized knives, like my EOD (Explosive Ordinance

Disposal), bomb-tech, haz-mat, and disaster rescue team knives. It is a

bit more complicated to sharpen in the field, but can be done by hand

with the right equipment. Example below.

- My Piranha

serrations have a smooth micro-edge but noticeable

alternating concave edges, one rounded, and one with an

internal chisel shaped square edge. This allows a

smoother cut than the Barracuda, but more aggressive

cutting than the micro-blade and improved trapping for

textiles, woods, and other fibrous materials. Sharpening

is a bit more difficult, as it requires a square edged

stone or rod to sharpen the square concavities. I also

offer this serration in a larger size for heavier duty

survival, combat, rescue, and emergency response knives.

See the Large Piranha example below.

- My Hammerhead

is a very large and substantial evolution of the

micro-blade, with deep concavities alternating with

chisel-knife edges that are very stout and strong. This

is a hardwood-gobbling tooth set that is very tough and

resilient, and unlikely to chip, break, or dull. Being

large, it's also easier to clean than tight or complex

geometries, increasing corrosion resistance and easing

blade care. It's very interesting that Gerber added my

serration type to their knives in 2008, after I had introduced

the serrations in my counterterrorism and Pararescue knives.

However, like most manufacturers, they did them wrong, with cuts

only from one side. This is because of the difficulty of

alignment of automated serration grinders, and thus, they are

too thick to be as effective as hand-cut serrations. My

hammerhead serrations are the main choice of my counterterrorism

teams. Example

below.

- A specialized serration I use is my

Theatre Curtain.

Like the draping theatre curtains of old-time stage shows, the

serration is a group of large convex grinds in a hollow ground

edge. These are not scallops; scallops are concave with

sharpened points, in essence my "Double Hollow" serrations

described just below. These are actually convex, so this is why

they are named "Theatre Curtain." There is some confusion here,

since only a couple knife manufacturers call this a "scalloped"

serration (Wusthof), but the main mass of knife manufacturers

describe "scalloped" as concave geometry of repeating cuts in

the blade with points, like my Double Hollow below. Currently, I'm only using this on my large bread knives,

as it aids greatly in piercing and slicing hard-crusted breads

while leaving a minimum of crumbs. If you're comparing

serrations, you'll notice that this type of convex

serration profile is coming up more and more in manufactured and

boutique shop knives. Examine them closely and you'll see that

they are poorly made, mostly ground on one side, making a

thicker, less sharp edge. This is because they are ground by

profile grinders, and they are never, ever as keen and thin as

serrations on the best handmade knives. Example below.

- A smaller version of my Theatre Curtain serrations is my

Mini-Curtain.

These are similar to the larger version, but much smaller.

Again, these are not scallops. They

are made in a hollow ground edge, and because of their size,

create few crumbs when cutting hard-loaf breads such as boules

and braided breads as well as filled breads (meats, fruits,

vegetables baked-in).

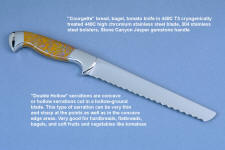

- In some kitchen knives, it helps to have extremely thin

serrations with gentle, sweeping curves. This is created in my

Double Hollow serrations. They are concave

(hollow) in profile, and ground into a hollow-ground blade, so

are extremely thin. They are useful for hard breads, flat

breads, bagels, and tomatoes as well as other vegetables.

- Other styles

are created individually, and I'm sure to create new ones.

I'll post and describe them here as they become available,

so please check back on the site, as it is continually

updated.

Page Topics

Please click on knife blade serration thumbnail photos

Barracuda

Vampire

Vampire

Canine

Micro-Blade

Theatre Curtain

Piranha

Large Piranha

Large Piranha

Hammerhead

Hammerhead

Hammerhead

Hammerhead

Mini-Curtain

Double-Hollow

With well-designed serrations, it is snagging that is the main

concern: trapping the blade and not being able to apply great

cutting force because the blade won't move.

Modern knife blade serrations are used as described above, for

tearing, ripping, and cutting through tough and stubborn textiles, wood,

bone, horn, and plastics, where ripping speed is more important than accuracy.

They are used on my tactical combat knives for trapping and severing tough cords,

ripping through materials, and in combat. They are used in chef's knives

for opening and piercing skins, crusts, and peeling.

You might read reviews by some that claim serrations

should be far out on the belly and near the point of the

knife blade, and not near the ricasso and handle. The theory

behind this is that you might need a tough sawing action

near the point, and a smooth cutting surface with more

control nearer the handle. This may have some merit if you

believe that you have greater or lesser control at a certain

position along the knife blade, but in most knives, control

of the blade is an issue based on the geometry of the blade

and handle, the size and weight of the blade, the hand strength

(or lack thereof) of the knife user, the nature of the

material being cut, and the actual task at hand.

All knives should be capable of being controlled,

whether they have serrations or not.

The most important reason to place serrations near the ricasso of the

knife is force and torque. Because serrations can hang, grab, and bite

into the material being cut, the knife user will apply more force to

make them move, free them up, and complete the cut. In combat knives,

this grabbing force and being able to control it is critical. Because of

mechanical leverage, more force and control can be applied to both use and free the

serration when the serration is nearest the handle.

If you don't believe me, try this experiment. Grab the end of a three

foot long bar of steel. Have a friend grab the bar with his hand very

near yours. Tell your friend to try to hold the bar horizontal, as you

try to force the bar to pivot downward. This will be very difficult.

Have your friend then grab the bar at the far end. Tell him to hold the

bar horizontal. It will be very easy for you to move the bar downward,

no matter how hard he grasps it. What this demonstrates is the simple

mechanics of a lever. The longer the lever arm, the less force it takes

to hold one end as the other is moved. This same force mechanics applies

to the serrations of a knife. If the serrations hang or trap, you must

be able to apply great force nearest the serrations to free them. If the

serrations are at the tip of the blade, they can bite and trap in

material, and you will not be able to transfer as much direct force to

free them. You must be able to free the serration or your knife blade is

trapped. To transfer the most energy and force, the serrations need to

be nearest the handle. This factor is easiest to realize in machine

tools. Cutters, mills, and saw blades are chosen and kept as short and

compact as possible to transfer the greatest amount of energy and

control to the cutting edge and limit flexing. Another critical factor

in knives is lateral flexion. If the blade is trapped at the tip in a

serration, and a sideways force is applied at the handle, the mechanical

leverage may be significant enough to snap the tip of the blade off.

There will be exceptions to this, of course. A good example is a

chef's knife that has a serration length at the tip to pierce skin

before slicing on the main blade. But this is a specialized knife and

not a combat weapon or tool, and is not expected to experience extreme

motion, forces, or impact.

Using serrations to cut depend on the knife, type of serrations, and

the task at hand. If they are sharp, great force is not necessary. For

example, with my Vampire serrations, usually the weight of the knife

blade alone with a back and forth sawing motion will cut through most

hardwoods, even rock maple. Most plastics give way easily to serrations,

and rope and line are easily severed with a twisting motion. This is another reason not to have tip serrations, as twisting a trapped

blade will most surely snap the serrated tip.

Some serrations are canted, that is, slanted in one direction. My

Patriot knife pattern typically has this type of serration. This allows

tremendous ripping force in one direction (pulling) while releasing in

the other (pushing). In a knife designed with canted serrations, it is

important to add extra features to apply even greater force to the

teeth. This is why the Patriot has a mid-quillon supported by a

mid-bolster (sub-hilt). This allows tremendous hand force to be applied

to the serration.

In my Micro-Blade serrations, a different type of cutting

action takes place. These are very smooth serrations,

interrupted sharp blades with deep, sharp hollows. This type

of serration is less likely to hang, but not as aggressive

on hardwoods and tough plastics.

The length of serrations varies, but I typically don't make

them any less than 1.5" of the blade run. This is because

any smaller than than are not enough teeth to engage the

cutting chore with sawing motion. If the style and geometry

of the blade permits it, I may make serrations along an

entire edge length. This may be different on each knife.

I rarely, if ever, create serrations that are both convex

and concave. This is typically what you will see on factory,

manufactured, and throwaway knives, and they are ground by

automated contoured wheels. Most people cannot sharpen these

mish-mash of geometries, and the long-term service of a fine

handmade knife should be considered. I want my clients to be

able to use and sharpen their works, over the life of the

blade, which should be decades. More on sharpening below.

Page Topics

Terrifying and sharp vampire rip tooth serrations on this "

PJSK

Viper"

Being able to sharpen a knife includes sharpening serrations.

It is not complicated, but simply a procedure of the regular maintenance of the knife.

"If i get 8 hours to cut a tree i'll spend 7 hours to sharp my knife."

--Abraham Lincoln

There are several good models of rod-type sharpeners for sharpening serrated knife blades.

Most of these are tapered, so will fit a wide variety of serrated grooves and edges. Like

a knife blade, the serrations should be sharpened when necessary, though this is much less

frequently than the main blade edge. The best rod-type sharpeners to use for the serrations are

diamond abrasive coated. Since these rods are usually tapered, they can fit a variety of

serration profiles. They can be used to sharpen line cutters, gut hooks, and even the

recurve area of some blades.

There are advantages and limitations for all types of diamond

abrasive coated rod sharpeners, and here are some comparisons. The rods

shown here are not all of the available types, and there are always new

ones.

Page Topics

Rod Sharpener Brands and Features

I've included some of the most common and accessible rod sharpeners here with some worthwhile facts for

you to consider. Prices for these sharpeners is modest, and at the time of this writing, they can be purchased

on various internet sites and sources from about $8.50 US to over $20.00 US. Details follow the picture above by

brand, from left to right.

- RUKO 040-CS Straight Combination Sharpening Rod: RUKO

(A Canadian Import Company and made in China) calls this a sharpening stick, and it has some

worthwhile features to consider, as well as limitations. The package

contains no instructions, only a list of "features." The rod is straight,

not tapered, so will not fit a variety of serration

profiles, only one, which is about .250 or 1/4", the main diameter

of the rod. It has a flat side, which can help in sharpening small

straight or possibly convex sections, and also a groove which can

sharpen fish hooks if you're so inclined. The large diameter rod

might be handy when sharpening gut hooks, large line cutters, and

even the recurve areas of some blades, and with finesse, you may be

able to sharpen combination convex-concave serrated pattern runs.

The package description claims it is a 4" Combination Diamond Rod,

but the actual measure of diamond coated rod that you can sharpen

with is less than 3.25"! The idea for the rod handle and storage is

decent: a cinch-type split barrel collet and a knurled ferrule

allows you to store the rod safely inside the aluminum barrel, which

has a tiny nickel plated pen clip. Unfortunately, on my model, I had

to bear down with some seriously hard pressure to get the body to

tighten on the rod, and even after I did, you could still tug it

from the holder because it grips on the smooth, polished, plated

part of the rod which is slick. The diamond abrasive particles are

claimed to be Medium 400 grit, so it's quite aggressive.

- RUKO 041-CS Combination Sharpening Rod: Like

the RUKO 040 above, this sharpening rod has several features and

limitations. The package contains no instructions, only a list of

"features." The actual rod has two sections, and is reversible. The

first section has the same geometry and diameter (.250") with a flat

side and a fish hook sharpening groove as the 040 detailed above. The other section has a

taper which runs from .250" to .075" diameter. An issue is their

description on the package card again, which claims the rod to be

4". The straight section is 2.5" long, and the tapered section is

2.5" long, so I don't know where they are getting their measurement.

Perhaps they should call it a 5" rod! The barrel/collet-knurled

ferrule holder grips much better than the 040 model, because the

smooth, nickel-plated section is small, and the diamond abrasive

coated particles will not allow the rod to easily slide. A drawback

would be the very short length of the tapered rod, which is so

abrupt a taper that you will be hard-pressed to get a 1/2" long

stroke for your serration sharpening geometry. The whole combination

idea is nice, though, so this sharpener might get you through the

widest variety of serration sharpening tasks on those knives that

have concave-convex serrations.

- Schrade: The Schrade serration rod

sharpener (made by Taylor Brands in China) Arrived

without even a descriptive card of features, in a box

with a folded paper insert describing their knives. I

have to note that the insert did have a section on

Resharpening Your Knife, but it did not mention anything about

sharpening serrations or even a word about the very sharpening rod

in the package. I have to go on here, because this is a bit

humorous. The sharpening description says, "hold the blade at a

107 to 157 angle from the surface of the sharpening stone" to

sharpen. I suppose that because this is printed in China, we are

supposed to understand, first, what a 157 angle is. Is that

degrees? Because if it is, this must mean an obtuse angle measured

from the side you are not sharpening... very confusing. Add to that

that the angle is all wrong, and 157° would

mean a 23° angle of the edge, the absolute maximum for sharpening.

This would mean that the 107° angle was actually 73° from the stone!

This would create a cutting edge that is nearly square, destroying

the knife blade and making it the dullest possible blade in history!

It's interesting to note that they spend twice the words in their

"Consumer Awareness Statement" warning the owner that they

are not responsible... okay, I couldn't help it; this is

typical of products with an American name being made in China. The rod is the

cheapest of all of these I'll describe, and it has some features

and limitations. A neat thing is the hard, rubber-ish pen-type

holder, which accommodates the rod for storage or use by

simple taper pressure. The actual rod is fairly short,

3" long, and has an abrupt taper from about .310" to

.050" which makes it way too abrupt to get that

important 1/2" long stroke. The rod has about a 1" long

groove for sharpening fish hooks, which is almost too

short for that. But if compact is what you want, and you

like short-stroking, this would be the cheapest route to

go. Like the RUKOs above, it has 400 grit diamond

abrasive.

- Lansky Diamond Tapered Sharpening Rod: This

company sells a lot of sharpening products, but

specifically, this diamond abrasive coated rod that they

call a "Rat Tail Sharpener" is what

I'll describe here. It's interesting to note that Lansky

boasts over and again in their company profile the size

and magnitude of their distribution

center, and that it is located in Henderson, Nevada.

You'll be hard-pressed to then find out that these products

are actually not made there, or even in this country. When I received the

clamshell package, a proud sticker was strategically

placed, claiming "Lansky Sharpeners- 30

Years-Quality and Innovation" Hidden underneath was

the required statement that these are actually made in

China. Did they place their sticker right over the "Made in

China" logo on purpose? Hmmm. Okay, this sharpener for serrations is a step in

the right direction. The rod is actually 3.5" long, and

has a more gentle and useable taper from .237" to

.067" in diameter, so that critical 1/2" long stroke is

more realistic than the previous types. The diamond

abrasive is finer, though they do not disclose the grit

size, merely claiming "Fine Grit." I'm guessing

it's about 600, but that's just a guess. They do include

instructions, but they are not specific, merely claiming

to "slide it straight down the rod with moderate

pressure." Repeating this process often enough and

you will destroy your serration profile. Advice: follow

the instructions below. For the handle, Lansky has

attached a butterfly (Balisong or fan) double pivot

knife style handle, so the rod folds into the handle

conveniently. The pivots are, unfortunately, plastic, so don't

expect this to last. The handle is a bit bulky, with ribbed

rubber grips that are really not necessary, particularly

since they are not in outer edge contact with your hand

when open, only when closed. But they are a convenient

place for the Chinese to place the Lansky name (distributed

in the US). The

handles have a little tab and slot arrangement to stop

them from sliding around when opened. This is a decent

serration sharpener, at a decent price.

- DMT DiaFold Serrated File: Made by

Diamond Machining Technology in Marlborough,

Massachusetts, this is an actual United States company

making fine diamond abrasive products right here in the

United States of America. They make many of the diamond

sharpening tools used in machine shops to sharpen and

touch up the hardest of machine tool cutters, inserts,

and ultra-hard edges. As you might expect, this is the

best serrated edge sharpener, and also the most

expensive, at about $20.00 US. The length of the rod is

just under 4.5" long, and the taper is a gentle one,

from .248" to .615" in diameter. So the critical 1/2"

long stroke is possible for a greater area than the

other models. The DMT serration files (file is a better

name, because that is what they are) are available in a

variety of grits: coarse, fine, and extra fine, so

tuning a serrated section from rough to extremely keen

is possible. The fine grit seems to be about 600. The

handle is a butterfly (Balisong or fan) style just like

the Lansky above, but has some nice features. The pivots

are steel roll pins, not plastic and the handle has

square detents and tabs that hold the sharpener both

closed and open. In the open position, it has a double

tab and socket to stop handle misalignment, and the tabs

are curved and deeper than the Lansky for smoother

indexing and a more solid fit. Though it is actually

larger than the Lansky, it weighs about the same (no

unnecessary rubbery grips). The DMT comes with ample instructions,

though not as detailed as I will give you below.

So, there are the players. You may be influenced by the size,

convenience, and carry possibilities of all these types, or you may

actually need a fish hook sharpener with you, so none of these are

exclusive.

By the way, as on the rest

of the site, I don't get paid to do these reviews, don't

receive free merchandise, exposure, or any benefit in

any way from any company or anyone. This is not an endorsement

of any kind, just a service I present to my clients, tradecraft and

anyone with knife interests.

Page Topics

Extremely sharp and aggressive Vampire rip-tooth serrations on

this PJLT

Position the knife parallel to and at the edge of a bench or table. Place the spine

of the knife (back of the blade) against the table, the point of the blade

away from you, and the serrated edge to be sharpened straight up.

Please click on photo to enlarge.

Determine the diameter of the serration on your knife. Lay the sharpening rod against the serrations

while looking down, and determine the area on the rod where the

circumference of the rod most closely fits the circumference of the

serration. On sharpening rods that have long handles, you may have to

position the handle overhanging the edge of the bench or table to see

this.

Please click on photo to enlarge.

Mark the rod. Once you have determined the location on the rod that matches the

curve of the serration, use a permanent marker (Sharpie® or other) to mark a girdle on the rod.

Continue the mark about ½" down the rod (toward the smaller end).

This girdled area will be where you contact the serration to sharpen

it. On some knives, the area being sharpened has a larger

circumference than the rod (such as gut hooks, line cutters, and

small recurve areas on the blade). In these cases, mark and use ½"

length of the largest diameter of the sharpening rod possible,

usually nearest the handle.

Please click on photo to enlarge.

Position

the rod at the sharpening angle. On polished or brightly

finished knives, you do not want to gouge or scratch the grind of

the serration, only the cutting edge. To do this, gently place the

rod, pointed end up, into the groove of the serration, feeling the

angle that the main serration is ground. Once you can feel that the rod is laying in the main grind of

the serration, lift the handle of the sharpening rod slightly. This

will establish the angle of the cutting edge that differs from the

main grind.

Sharpen. Lightly move the rod forward and backward

along your ½" marked girdle to cut the edge of the serration. Do not

use heavy pressure. Diamond abrasives work best at a light pressure,

and no lubrication is necessary on any diamond sharpener. Do not lower the handle, or the diamond

rod will scratch the main serration grind. Maintain the sharpening

angle as accurately as possible.

Please click on photo to enlarge.

Repeat the same positioning technique and sharpen

the other side of the serration if the serration has one. Some

knives are only ground on one side of the serration.

Remove the

burr. If you have done this properly, you can see or feel a tiny

burr on the opposite of the last side you sharpened. Now, only using

one light ½" stroke, sharpen off the burr. The serration should now

be sharp.

Please click on photo to enlarge.

Wider serrations. Some serrations are wider than the circumference of

the rod. Gut hooks, hook-blades, line cutters and other specially shaped

large diameter profiles on knife blades are often of a larger diameter

than the rod. To sharpen with a smaller diameter rod, use the largest

diameter of the rod, usually near the handle. Establish the angle as

above, and when sharpening move the rod along the entire edge, twisting

the rod with your hand as you sharpen. This twisting motion will help

prevent waviness on the cutting edge. It takes a little practice to get

a smooth cut; take your time and clean up the burr for a final smooth

edge.

Sharpening Theatre Curtain Serrations

(including my Mini-Curtain) are a special case, and people often wonder

how these are sharpened. The first thing to consider is that I use a

high precision, extended, and complex heat treating cryogenic method

that results in a blade that is in the pinnacle of condition. To the

chef, this means that a curtain serration will unlikely ever need

sharpening in his lifetime. These knives are not like manufactured

knives or other maker's knives made from poor, plain carbon,

pattern-welded (decor) damascus, or low alloy steels. They do not

require constant sharpening to stay tuned up and ready to cut, and that

is the first point.

However, after a generation of use, a curtain-serrated knife might

need sharpened. To do this, the spine is taped off for protection from

scratches, and several light draws with a diamond abrasive micro file is

all it takes to bring them back to maximum sharpness. These files (the

flat side of the half-round, the three-square and the square) will work into the V-grooves and over the

convex areas easily. Just follow the original angles, and finish exactly

like the concave serrations above. Just make sure the abrasive is diamond, as ceramic

and other stones won't sharpen these T3 cryogenically treated knives!

Since it will probably be your grandkids that receive these knives,

they might appreciate this information, long after you (and I) are gone.

So I'll be sure to leave a copy in the Library of Congress so that they

can look it up!

Page Topics

Wide and deep angled line cutter on this

Flamesteed